In this post I will be talking about some of the basic field-based tools that one can use which will assist in building a shared understanding with the participants of the research process. By field-based tools I mean tools which can be used while collecting data in the field.

Firstly, there is 'mapping the landscape'. Mapping the landscape gives people a shared “bird’s eye view of landscape. It is usefulfor arriving at an understanding regarding boundaries, nature and scope potential research projects.

Secondly, there are 'field trips'. Field trips allows the moving of sometimes contentious and abstract discussions based on differentperspectives to a concrete, site specific context as a basis for common understanding. It issuitable for field-based research projects such as thinning or harvest methods and their impacts.

Thirdly, there is 'citizen monitoring' - this is not what the NSA does, by the way. Citizen monitoring is defined as involving community members in assessing environmental and/orsocial change over time. This can be a tool both for gathering critical data, and also forraising consciousness about common problems and opportunities.

Sunday, 15 December 2013

Thursday, 21 November 2013

Semi-structured interviewing as a data collection method in PR

I've already mentioned doing interviews a couple times in the previous posts, but this entry will be dedicated to the topic itself. Semi-structured interviews are one of the main tools used in participatory research approaches, The reason why this method is called 'semi-structured' interviews, is because the questions determined a priori to the actual interview are merely used as a guide for the researcher, not a strict list that must be followed. Many of the questions are determined in the midst of the interview itself, determined by what the participant wants to talk about and what seems interesting to the researcher. Sometimes, the questions that are written before hand are deemed irrelevant in the particular interview, and can thus be skipped if the researcher thinks this is so.

There are two specific types of interviews that can be used effectively in participatory research; these are (a) individual semi-structured interviews and (b) key informant emi-structured interviews. I'll start off, as most people do, with (a).

Individual interviews are used to obtain representative information. As information that is obtained from individual interviews is more personal when compared to group interviews (for obvious reasons) it has a higher probability of revealing conflicts within the community as respondents may feel that can speak more freely without their neighbors present. One should attempt to interview as broadly representative a sample as possible; as participatory research places emphasis on those individuals who are at the very bottom of the society in which they are working, these individuals must be included in the interviews as well. One can also interview random people that happen to pass-by the researchers as these may reveal useful information and unexpected viewpoints.

The other type of interview that I will be talking about are interviews with individuals who are deemed 'key informants'. These types of semi-structured interviews are used to obtain special knowledge, as a key informant is anyone who has a special knowledge on a particular topic (such as a merchant on transportation and credit, midwife on birth control practices, or farmers on agricultural practices). Key informants are expected to be able to answer questions about the knowledge and behavior of others and specially about the operations of the broader systems in which the individual and their community is immersed. While it is possible that the information garnered by key informants may be misleading, they are still a may possible source of information for the participatory researcher. Valuable key informants are outsiders who live in the specific community, such as teachers or doctors, people from different communities, and individuals that have 'married in' to the community. They types of individuals usually have a more distanciated perspective on the practices within the community, and can thus offer more objective information on the community than the community members.

Thus concludes this post on semi-structured interviews and how they are essential to collecting data using the participatory research approach. This post was by no means a comprehensive account of interviews, as they are unexpectedly complex things to do correctly - however, it was just a basic idea of what they can provide a good researcher.

There are two specific types of interviews that can be used effectively in participatory research; these are (a) individual semi-structured interviews and (b) key informant emi-structured interviews. I'll start off, as most people do, with (a).

Individual interviews are used to obtain representative information. As information that is obtained from individual interviews is more personal when compared to group interviews (for obvious reasons) it has a higher probability of revealing conflicts within the community as respondents may feel that can speak more freely without their neighbors present. One should attempt to interview as broadly representative a sample as possible; as participatory research places emphasis on those individuals who are at the very bottom of the society in which they are working, these individuals must be included in the interviews as well. One can also interview random people that happen to pass-by the researchers as these may reveal useful information and unexpected viewpoints.

The other type of interview that I will be talking about are interviews with individuals who are deemed 'key informants'. These types of semi-structured interviews are used to obtain special knowledge, as a key informant is anyone who has a special knowledge on a particular topic (such as a merchant on transportation and credit, midwife on birth control practices, or farmers on agricultural practices). Key informants are expected to be able to answer questions about the knowledge and behavior of others and specially about the operations of the broader systems in which the individual and their community is immersed. While it is possible that the information garnered by key informants may be misleading, they are still a may possible source of information for the participatory researcher. Valuable key informants are outsiders who live in the specific community, such as teachers or doctors, people from different communities, and individuals that have 'married in' to the community. They types of individuals usually have a more distanciated perspective on the practices within the community, and can thus offer more objective information on the community than the community members.

Thus concludes this post on semi-structured interviews and how they are essential to collecting data using the participatory research approach. This post was by no means a comprehensive account of interviews, as they are unexpectedly complex things to do correctly - however, it was just a basic idea of what they can provide a good researcher.

Monday, 18 November 2013

Venn diagram exercise in participatory research

I haven't used this activity myself in research, but I can appreciate the value it may bring to the data collection process. As such, I will be merely explaining how one can go about using it instead of discussing it within an example itself.

To begin with, a Venn diagram (named after the man who came up with the concept) showed the key institutions and individuals in a community, as well as their relationships and importance for decision-making. It must be noted, however, that Venn diagrams may be a difficult concept to understand for those who have not been exposed to them before; be sure that everyone who is participating in the exercise fully understands the concept behind what they are doing.

There are multiple steps in the process of creating a Venn diagram, but the process of the participants constructing the diagram, as well as the end result of the diagram itself are both very rich sources of information. A basic structure of the steps to be taken when conducting a Venn diagram maximizing participation are as follows:

(1) Identify key institutions responsible for decisions in a community or organization;

(2) Identify the degree of contact and overlap between them in terms of decision-making. Overlap occurs if one institution asks or tells another to do something or if they have to cooperate in some way;

(3) Obtain information from secondary sources, group interviews, or from key informants;

(4) Cut out (or draw) circles to represent each institution or individual;

(5) Size of circles indicates importance or scope (separate circles = no contact; touching circles = information passes between institutions; small overlap = some cooperation in decision making; large overlap = considerable cooperation in decision making);

(6) Draw the Venn diagram first in pencil and adjust the size or arrangement of circles until the representation is accurate; when everyone is satisfied that it is accurate, go over it with a marker to make it more visible and easier to read;

(7) Encourage community members to draw their own Venn diagrams and compare them.

The image below is an example of a Venn diagram drawn by participants in a participatory research project on village water use and control in Sudan (not sure if it was in the north or south now though).

To begin with, a Venn diagram (named after the man who came up with the concept) showed the key institutions and individuals in a community, as well as their relationships and importance for decision-making. It must be noted, however, that Venn diagrams may be a difficult concept to understand for those who have not been exposed to them before; be sure that everyone who is participating in the exercise fully understands the concept behind what they are doing.

There are multiple steps in the process of creating a Venn diagram, but the process of the participants constructing the diagram, as well as the end result of the diagram itself are both very rich sources of information. A basic structure of the steps to be taken when conducting a Venn diagram maximizing participation are as follows:

(1) Identify key institutions responsible for decisions in a community or organization;

(2) Identify the degree of contact and overlap between them in terms of decision-making. Overlap occurs if one institution asks or tells another to do something or if they have to cooperate in some way;

(3) Obtain information from secondary sources, group interviews, or from key informants;

(4) Cut out (or draw) circles to represent each institution or individual;

(5) Size of circles indicates importance or scope (separate circles = no contact; touching circles = information passes between institutions; small overlap = some cooperation in decision making; large overlap = considerable cooperation in decision making);

(6) Draw the Venn diagram first in pencil and adjust the size or arrangement of circles until the representation is accurate; when everyone is satisfied that it is accurate, go over it with a marker to make it more visible and easier to read;

(7) Encourage community members to draw their own Venn diagrams and compare them.

The image below is an example of a Venn diagram drawn by participants in a participatory research project on village water use and control in Sudan (not sure if it was in the north or south now though).

Friday, 15 November 2013

Using a mapping exercise in participatory research

In this post, I will be talking about how one can use a mapping exercise in participatory research to gather data whilst maximizing participant participation in the research process. This exercise also makes full use of local perspectives and local knowledge, which is essential to the PR process, as I've already discussed in previous posts. I will, again, be using examples and images from some of my own research.

Mapping is a form of visual based data gathering usually through the use of pictures and symbolic indicators. This usually entails mapping out a community; this includes buildings, services, roads and communal areas. Participatory researchers have discussed the many ways in which maps can be used, such as to draw the spatial arrangement of houses. Mobility maps are used to identify the spatial mobility of communities or to access local knowledge on how people perceive their resources and places in their communities. Some see this commonly used method as a way in which participants construct and present their views. This tool also allows for participation of the entire group as it usually promotes discussion and the researchers can gain insight into the way participants generate ideas and then produce the information they want to include.

For the research I will be using as an example, the participants were asked to draw a map representing where all their money ‘went’, in other words where their money was spend or used and to represent it on a map, indicating how far or near they perceived these places to be. This technique was implemented in order to gain an overall perspective on where participants spend and use their money and also to generate discussion about how close or far these areas are considered to be.

During the process, the translator introduced the mapping exercise to the group of participants. Once again Participant 1 (as mentioned in the last post) took a leadership role and generated a discussion among the group in order to construct the map and answer the questions the researchers asked. At first the participants laughed as no one wanted the responsibility of drawing a map, after discussion Participant 1 and one other participant chose to use the paper and marker pens to create the map. The younger participant was recruited by the rest of the group to help as it seems she was able to write in English. The participants began by drawing roads and then buildings and houses, the younger participant then decided to label these areas after the researchers asked them to symbolically represent what they were drawing so to identify them. Although only two participants drew the map, Participant 1 consistently validated what was being drawn and referred back to the rest of the group.

As the above paragraphs imply, this research was heavily reliant on the participants knowledge and participation in the activity. Thus, the researcher's role was primarily one of observation and minimal facilitation. Again, this exercise enabled the researcher (me) to gain quite a lot of insight into the way the participants perceived their own monetary travelling. The original map was converted into a electronic version, which is a bit more clear - i've added this image below.

Mapping is a form of visual based data gathering usually through the use of pictures and symbolic indicators. This usually entails mapping out a community; this includes buildings, services, roads and communal areas. Participatory researchers have discussed the many ways in which maps can be used, such as to draw the spatial arrangement of houses. Mobility maps are used to identify the spatial mobility of communities or to access local knowledge on how people perceive their resources and places in their communities. Some see this commonly used method as a way in which participants construct and present their views. This tool also allows for participation of the entire group as it usually promotes discussion and the researchers can gain insight into the way participants generate ideas and then produce the information they want to include.

For the research I will be using as an example, the participants were asked to draw a map representing where all their money ‘went’, in other words where their money was spend or used and to represent it on a map, indicating how far or near they perceived these places to be. This technique was implemented in order to gain an overall perspective on where participants spend and use their money and also to generate discussion about how close or far these areas are considered to be.

During the process, the translator introduced the mapping exercise to the group of participants. Once again Participant 1 (as mentioned in the last post) took a leadership role and generated a discussion among the group in order to construct the map and answer the questions the researchers asked. At first the participants laughed as no one wanted the responsibility of drawing a map, after discussion Participant 1 and one other participant chose to use the paper and marker pens to create the map. The younger participant was recruited by the rest of the group to help as it seems she was able to write in English. The participants began by drawing roads and then buildings and houses, the younger participant then decided to label these areas after the researchers asked them to symbolically represent what they were drawing so to identify them. Although only two participants drew the map, Participant 1 consistently validated what was being drawn and referred back to the rest of the group.

As the above paragraphs imply, this research was heavily reliant on the participants knowledge and participation in the activity. Thus, the researcher's role was primarily one of observation and minimal facilitation. Again, this exercise enabled the researcher (me) to gain quite a lot of insight into the way the participants perceived their own monetary travelling. The original map was converted into a electronic version, which is a bit more clear - i've added this image below.

Thursday, 14 November 2013

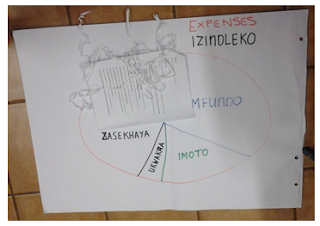

Using pie charts in participatory research

In this post I will be talking about the pie chart exercise as a method which one can gather data from when conducting participatory research. I will be using pictures and examples from some of my own research that I have conducted recently.

Pie charts are visual methods used to demonstrate the distribution of various resources in relation to others. It can be a useful tool for evaluation and by using non-permeable materials it allows for flexibility, change and correction. By making use of a visual representation it includes participants who are not literate and gives them the opportunity to still be involved. It is even more useful when a language barrier exists between the researchers and participants as the data collected will be diagrammatically represented. In addition to allowing all participants to contribute to the process is it most valuable in obtaining social information.

For the study I am using as an example, the participants were asked to construct two pie charts. The first pie chart represented income, which included any sources from which the participants received their money, the second represented expenses or use of money. The translator (as these participants spoke isiZulu and I speak English) explained the process to the participants and before the exercise one of the researchers and a translator drew an example of a pie chart. As I was inside a hall instead of outside, we supplied the participants with string, prestik, masking tape and stones; however, this activity has been done before with merely sticks and sand.

The income and expenditure pie charts were used to immediately gain information about the use of money in the group. This activity would allow for further discussion based on the results as well as to inform the researchers of the variables of importance from the outset our study.

After explaining the process and leaving the materials with the group, I stepped back and allowed the participants to discuss the task (notice the concept of distanciation in action here). One participant (which we will refer to as Participant 1) took a leadership role and decided to generate a discussion among the group members. The translator and one researcher translated back to the other researchers while the participants were discussing the pie charts.

This exercise can also be used in conjunction with other activities, such as focus groups. This is what I did in my research; I asked the group to first discuss the issue, and then to visualize what they had talked about in the forms illustrated above. As you can see by the illustrations, this activity was very informal and done almost completely by the participants – yet the data retrieved from observing the group as well as the data produced by the charts was vital to this projects analysis.

Pie charts are visual methods used to demonstrate the distribution of various resources in relation to others. It can be a useful tool for evaluation and by using non-permeable materials it allows for flexibility, change and correction. By making use of a visual representation it includes participants who are not literate and gives them the opportunity to still be involved. It is even more useful when a language barrier exists between the researchers and participants as the data collected will be diagrammatically represented. In addition to allowing all participants to contribute to the process is it most valuable in obtaining social information.

For the study I am using as an example, the participants were asked to construct two pie charts. The first pie chart represented income, which included any sources from which the participants received their money, the second represented expenses or use of money. The translator (as these participants spoke isiZulu and I speak English) explained the process to the participants and before the exercise one of the researchers and a translator drew an example of a pie chart. As I was inside a hall instead of outside, we supplied the participants with string, prestik, masking tape and stones; however, this activity has been done before with merely sticks and sand.

The income and expenditure pie charts were used to immediately gain information about the use of money in the group. This activity would allow for further discussion based on the results as well as to inform the researchers of the variables of importance from the outset our study.

After explaining the process and leaving the materials with the group, I stepped back and allowed the participants to discuss the task (notice the concept of distanciation in action here). One participant (which we will refer to as Participant 1) took a leadership role and decided to generate a discussion among the group members. The translator and one researcher translated back to the other researchers while the participants were discussing the pie charts.

This exercise can also be used in conjunction with other activities, such as focus groups. This is what I did in my research; I asked the group to first discuss the issue, and then to visualize what they had talked about in the forms illustrated above. As you can see by the illustrations, this activity was very informal and done almost completely by the participants – yet the data retrieved from observing the group as well as the data produced by the charts was vital to this projects analysis.

Ensuring rigor in participatory research

I know I said I will start discussing some techniques in the last post, but I forgot about the theory behind ensuring rigor in participatory research. Because scientific rigor is linked to the positivisitc approach, it is necessary to somewhat change the process of validity and reality when conducting participatory research. This is what will be discussed in the following post.

A challenge that arises in qualitative research is in assuring the quality and trustworthiness of research. A researcher may hope that the quality of research craftsmanship produces knowledge claims that are so powerful and convincing in their own right they carry the validation with them, like a strong piece of art. However, seldom does this actually occur. The value of qualitative research must be argued for and justified against established quantitative criteria. If lacking in this, qualitative researchers subject themselves to criticism from positivists who claim that qualitative research is merely a subjective assertion supported by unscientific method.

The concepts of reliability, validity and generalizability provide the fundamental framework for conducting and evaluating traditional quantitative research. Qualitative researchers however argue against these criteria, stating them as being reductionist and misinterpretative of the complex and diverse system of interrelationships. Consequently, they have instead replaced them with alternative criteria developed in response to their specific research ideals. This criteria includes ‘rigor’.

Rigor in qualitative research is often synonymous with the quantitative notion of validity. Validity is the degree to which research truly measures what it intends to measure. This criterion is based upon the supposition that the phenomena being measured possess ‘reality’ in an undisputed and objective sense. However, qualitative research argues that given the social world, it is inaccurate to assume the existence of one unequivocal reality to which all findings must respond. The question it raises instead is whose reality is the research addressing? .

By definition qualitative research is about ‘subjective interpretation’. PR enhances the validity of research through its participation of stakeholders. According to PR, since people are continually acting in the world in relation to others, human action is essentially social. Human action is viewed as a dialogical and dialectical process which seeks to access multiple voices and perspectives. Constructions of reality are viewed as being manifested through the reflective action of people and communities.

In PR subjects of the research are active participants throughout the research process. This procedure ensures validity by preventing the possibility of researchers to observe and interpret findings through the lens of their own interpretive frameworks. Hence, the theorizing of phenomena is not de-contextualized but rather fixed in individuals’ experiences and in their web of meanings. The integrity of the research process as well as the quality of the end product is based upon principles that allow a researcher to“acknowledge that trust and truth are fragile, while enabling them to engage with the messiness and complexity of data interpretation in ways that reflect the lives of participants. That is, valid research should take into account the sociality of human action and address the participative, relational and social aspects.

A much greater degree of validity is attained in PR when research participants are allowed to check the veracity of the material. This means that participants are provided feedback whereby they engage with the material and verify its accuracy. Through this verification process participants help formulate accounts that accurately represent their own experiences and perspectives. The validity of PR therefore exists within its joint and experiential nature, that is, valid research should be a reflection of an interpretation of human action.

Furthermore, PR is dependent on the level of practicality and the degree to which it engages within its socially valuable work. This is referred to as pragmatic validity, whereby in PR the practicality in the context of research is valued. The essential “truth” of the research pertains to the notion of research generating not only individualistic but institutional change. Thus, the concept of validity in PR has been broadened to accommodate a socially conscious and emancipatory discourse.

Another aim in PR is for it to demonstrate catalytic validity. Research that possesses catalytic validity is said to not only display the reality- altering impact of the inquiry process, it also directs this impact so that those under study will gain self- understanding and self- direction. In other words, PR should exhibit conscientization and display emancipatory intent. This means that the research should move those it studies in order understand the world and should be shaped in such a manner as to transform it.

A challenge that arises in qualitative research is in assuring the quality and trustworthiness of research. A researcher may hope that the quality of research craftsmanship produces knowledge claims that are so powerful and convincing in their own right they carry the validation with them, like a strong piece of art. However, seldom does this actually occur. The value of qualitative research must be argued for and justified against established quantitative criteria. If lacking in this, qualitative researchers subject themselves to criticism from positivists who claim that qualitative research is merely a subjective assertion supported by unscientific method.

The concepts of reliability, validity and generalizability provide the fundamental framework for conducting and evaluating traditional quantitative research. Qualitative researchers however argue against these criteria, stating them as being reductionist and misinterpretative of the complex and diverse system of interrelationships. Consequently, they have instead replaced them with alternative criteria developed in response to their specific research ideals. This criteria includes ‘rigor’.

Rigor in qualitative research is often synonymous with the quantitative notion of validity. Validity is the degree to which research truly measures what it intends to measure. This criterion is based upon the supposition that the phenomena being measured possess ‘reality’ in an undisputed and objective sense. However, qualitative research argues that given the social world, it is inaccurate to assume the existence of one unequivocal reality to which all findings must respond. The question it raises instead is whose reality is the research addressing? .

By definition qualitative research is about ‘subjective interpretation’. PR enhances the validity of research through its participation of stakeholders. According to PR, since people are continually acting in the world in relation to others, human action is essentially social. Human action is viewed as a dialogical and dialectical process which seeks to access multiple voices and perspectives. Constructions of reality are viewed as being manifested through the reflective action of people and communities.

In PR subjects of the research are active participants throughout the research process. This procedure ensures validity by preventing the possibility of researchers to observe and interpret findings through the lens of their own interpretive frameworks. Hence, the theorizing of phenomena is not de-contextualized but rather fixed in individuals’ experiences and in their web of meanings. The integrity of the research process as well as the quality of the end product is based upon principles that allow a researcher to“acknowledge that trust and truth are fragile, while enabling them to engage with the messiness and complexity of data interpretation in ways that reflect the lives of participants. That is, valid research should take into account the sociality of human action and address the participative, relational and social aspects.

A much greater degree of validity is attained in PR when research participants are allowed to check the veracity of the material. This means that participants are provided feedback whereby they engage with the material and verify its accuracy. Through this verification process participants help formulate accounts that accurately represent their own experiences and perspectives. The validity of PR therefore exists within its joint and experiential nature, that is, valid research should be a reflection of an interpretation of human action.

Furthermore, PR is dependent on the level of practicality and the degree to which it engages within its socially valuable work. This is referred to as pragmatic validity, whereby in PR the practicality in the context of research is valued. The essential “truth” of the research pertains to the notion of research generating not only individualistic but institutional change. Thus, the concept of validity in PR has been broadened to accommodate a socially conscious and emancipatory discourse.

Another aim in PR is for it to demonstrate catalytic validity. Research that possesses catalytic validity is said to not only display the reality- altering impact of the inquiry process, it also directs this impact so that those under study will gain self- understanding and self- direction. In other words, PR should exhibit conscientization and display emancipatory intent. This means that the research should move those it studies in order understand the world and should be shaped in such a manner as to transform it.

Wednesday, 13 November 2013

Challenges in participatory research

As hinted at in the last post, there are many challenges that participatory research and its practitioners must face. Mainly, these challenges have arisen because this research approach is relatively young and still needs to work out some 'kinks'. Some of these challenges will be discussed in the forthcoming post.

As some participatory researchers assert, it is common to hear of participatory researchers expressing frustration on the part of the community being apathetic towards the research process; thus, non-interest or apathy on behalf of the community is a challenge that PR practitioners must face. Participatory researchers also face a dilemma between building the capacity of the community as much as possible and report back to the research funders on the progress of the project; whilst educating funding agencies on the benefits of PR may make them more amiable to participatory research and true capacity building, this is currently a challenge PR faces.

Some of the core principles in PR, such as rapport building, often take a long time and thus can be constrained by lack of time and financial resources. Also concerning the financial resources of some PR phases, such as rapport building, are less likely to be supported by funders as they may not see it as an important part of the research process and thus it is up to the researchers to convince them of its importance. Although there is a focus on the ‘dispossessed’ (such as young children, the elderly, women) members of the community, many of the people do not end up being part of the research process and, subsequently, possibly vital sources of information are lost.

There may be participants who do not trust the researchers or feel that they have nothing to gain from participating in the activities and the overall research process often choose not to be involved in them at all, and, again, this is a loss of important information. Last in this itinerary of challenges, but not the least of them, is the issue of the lingering unbalanced power dynamics among the participants and the researchers, even if participation has been increased.

To conclude the posts i've written so far, it is evident from what was discussed that the participatory approach to conducting research is, at its core, fundamentally different from other research approaches, specifically that of positivism. For example, in contrast to the principles and concepts of conducting positivistic research, such as the researcher being a distant, disconnected, neutral entity who only looks at empirical sources of information and indirectly reinforces unequal power dynamics in research, the participatory researcher believes in the principles of verstehen and distanciation, maximizing the role of the participants in the research in order to make use of their own local knowledge so as to decrease the power dynamics between researchers and participants and to maximize the chance of sustainable empowerment in the community they are working with.

The participatory approach also adopts some principles from the social approach to understand human action, such as the fact that individuals are not always aware of the meaning and reason behind their own actions and that in order to understand an action; one must understand the cultural and social conventions and institutions that indirectly determine the intent of the action. The ontological (nature of reality) and epistemological (nature of knowledge) structure of the participatory approach and subsequently how knowledge, using the participatory approach, is generated. Lastly, in this post, some of the challenges of the PR approach – which appeared to be primarily practical issues – were discussed. In the subsequent posts, I will be discussing certain participatory research techniques that can be used which maximize participant participation.

As some participatory researchers assert, it is common to hear of participatory researchers expressing frustration on the part of the community being apathetic towards the research process; thus, non-interest or apathy on behalf of the community is a challenge that PR practitioners must face. Participatory researchers also face a dilemma between building the capacity of the community as much as possible and report back to the research funders on the progress of the project; whilst educating funding agencies on the benefits of PR may make them more amiable to participatory research and true capacity building, this is currently a challenge PR faces.

Some of the core principles in PR, such as rapport building, often take a long time and thus can be constrained by lack of time and financial resources. Also concerning the financial resources of some PR phases, such as rapport building, are less likely to be supported by funders as they may not see it as an important part of the research process and thus it is up to the researchers to convince them of its importance. Although there is a focus on the ‘dispossessed’ (such as young children, the elderly, women) members of the community, many of the people do not end up being part of the research process and, subsequently, possibly vital sources of information are lost.

There may be participants who do not trust the researchers or feel that they have nothing to gain from participating in the activities and the overall research process often choose not to be involved in them at all, and, again, this is a loss of important information. Last in this itinerary of challenges, but not the least of them, is the issue of the lingering unbalanced power dynamics among the participants and the researchers, even if participation has been increased.

To conclude the posts i've written so far, it is evident from what was discussed that the participatory approach to conducting research is, at its core, fundamentally different from other research approaches, specifically that of positivism. For example, in contrast to the principles and concepts of conducting positivistic research, such as the researcher being a distant, disconnected, neutral entity who only looks at empirical sources of information and indirectly reinforces unequal power dynamics in research, the participatory researcher believes in the principles of verstehen and distanciation, maximizing the role of the participants in the research in order to make use of their own local knowledge so as to decrease the power dynamics between researchers and participants and to maximize the chance of sustainable empowerment in the community they are working with.

The participatory approach also adopts some principles from the social approach to understand human action, such as the fact that individuals are not always aware of the meaning and reason behind their own actions and that in order to understand an action; one must understand the cultural and social conventions and institutions that indirectly determine the intent of the action. The ontological (nature of reality) and epistemological (nature of knowledge) structure of the participatory approach and subsequently how knowledge, using the participatory approach, is generated. Lastly, in this post, some of the challenges of the PR approach – which appeared to be primarily practical issues – were discussed. In the subsequent posts, I will be discussing certain participatory research techniques that can be used which maximize participant participation.

Labels:

Action,

Background,

Challenges in PR,

Commonsense psychology,

Conclusion,

Empistemology,

Empowerment,

Folk Psychology,

Human Action,

Humanism,

Introduction,

Knowledge,

Ontology,

Participatory Research,

Social

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)