In this post I will be talking about some of the basic field-based tools that one can use which will assist in building a shared understanding with the participants of the research process. By field-based tools I mean tools which can be used while collecting data in the field.

Firstly, there is 'mapping the landscape'. Mapping the landscape gives people a shared “bird’s eye view of landscape. It is usefulfor arriving at an understanding regarding boundaries, nature and scope potential research projects.

Secondly, there are 'field trips'. Field trips allows the moving of sometimes contentious and abstract discussions based on differentperspectives to a concrete, site specific context as a basis for common understanding. It issuitable for field-based research projects such as thinning or harvest methods and their impacts.

Thirdly, there is 'citizen monitoring' - this is not what the NSA does, by the way. Citizen monitoring is defined as involving community members in assessing environmental and/orsocial change over time. This can be a tool both for gathering critical data, and also forraising consciousness about common problems and opportunities.

Showing posts with label Local Knowledge. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Local Knowledge. Show all posts

Sunday, 15 December 2013

Monday, 18 November 2013

Venn diagram exercise in participatory research

I haven't used this activity myself in research, but I can appreciate the value it may bring to the data collection process. As such, I will be merely explaining how one can go about using it instead of discussing it within an example itself.

To begin with, a Venn diagram (named after the man who came up with the concept) showed the key institutions and individuals in a community, as well as their relationships and importance for decision-making. It must be noted, however, that Venn diagrams may be a difficult concept to understand for those who have not been exposed to them before; be sure that everyone who is participating in the exercise fully understands the concept behind what they are doing.

There are multiple steps in the process of creating a Venn diagram, but the process of the participants constructing the diagram, as well as the end result of the diagram itself are both very rich sources of information. A basic structure of the steps to be taken when conducting a Venn diagram maximizing participation are as follows:

(1) Identify key institutions responsible for decisions in a community or organization;

(2) Identify the degree of contact and overlap between them in terms of decision-making. Overlap occurs if one institution asks or tells another to do something or if they have to cooperate in some way;

(3) Obtain information from secondary sources, group interviews, or from key informants;

(4) Cut out (or draw) circles to represent each institution or individual;

(5) Size of circles indicates importance or scope (separate circles = no contact; touching circles = information passes between institutions; small overlap = some cooperation in decision making; large overlap = considerable cooperation in decision making);

(6) Draw the Venn diagram first in pencil and adjust the size or arrangement of circles until the representation is accurate; when everyone is satisfied that it is accurate, go over it with a marker to make it more visible and easier to read;

(7) Encourage community members to draw their own Venn diagrams and compare them.

The image below is an example of a Venn diagram drawn by participants in a participatory research project on village water use and control in Sudan (not sure if it was in the north or south now though).

To begin with, a Venn diagram (named after the man who came up with the concept) showed the key institutions and individuals in a community, as well as their relationships and importance for decision-making. It must be noted, however, that Venn diagrams may be a difficult concept to understand for those who have not been exposed to them before; be sure that everyone who is participating in the exercise fully understands the concept behind what they are doing.

There are multiple steps in the process of creating a Venn diagram, but the process of the participants constructing the diagram, as well as the end result of the diagram itself are both very rich sources of information. A basic structure of the steps to be taken when conducting a Venn diagram maximizing participation are as follows:

(1) Identify key institutions responsible for decisions in a community or organization;

(2) Identify the degree of contact and overlap between them in terms of decision-making. Overlap occurs if one institution asks or tells another to do something or if they have to cooperate in some way;

(3) Obtain information from secondary sources, group interviews, or from key informants;

(4) Cut out (or draw) circles to represent each institution or individual;

(5) Size of circles indicates importance or scope (separate circles = no contact; touching circles = information passes between institutions; small overlap = some cooperation in decision making; large overlap = considerable cooperation in decision making);

(6) Draw the Venn diagram first in pencil and adjust the size or arrangement of circles until the representation is accurate; when everyone is satisfied that it is accurate, go over it with a marker to make it more visible and easier to read;

(7) Encourage community members to draw their own Venn diagrams and compare them.

The image below is an example of a Venn diagram drawn by participants in a participatory research project on village water use and control in Sudan (not sure if it was in the north or south now though).

Thursday, 14 November 2013

Using pie charts in participatory research

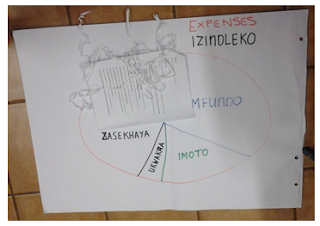

In this post I will be talking about the pie chart exercise as a method which one can gather data from when conducting participatory research. I will be using pictures and examples from some of my own research that I have conducted recently.

Pie charts are visual methods used to demonstrate the distribution of various resources in relation to others. It can be a useful tool for evaluation and by using non-permeable materials it allows for flexibility, change and correction. By making use of a visual representation it includes participants who are not literate and gives them the opportunity to still be involved. It is even more useful when a language barrier exists between the researchers and participants as the data collected will be diagrammatically represented. In addition to allowing all participants to contribute to the process is it most valuable in obtaining social information.

For the study I am using as an example, the participants were asked to construct two pie charts. The first pie chart represented income, which included any sources from which the participants received their money, the second represented expenses or use of money. The translator (as these participants spoke isiZulu and I speak English) explained the process to the participants and before the exercise one of the researchers and a translator drew an example of a pie chart. As I was inside a hall instead of outside, we supplied the participants with string, prestik, masking tape and stones; however, this activity has been done before with merely sticks and sand.

The income and expenditure pie charts were used to immediately gain information about the use of money in the group. This activity would allow for further discussion based on the results as well as to inform the researchers of the variables of importance from the outset our study.

After explaining the process and leaving the materials with the group, I stepped back and allowed the participants to discuss the task (notice the concept of distanciation in action here). One participant (which we will refer to as Participant 1) took a leadership role and decided to generate a discussion among the group members. The translator and one researcher translated back to the other researchers while the participants were discussing the pie charts.

This exercise can also be used in conjunction with other activities, such as focus groups. This is what I did in my research; I asked the group to first discuss the issue, and then to visualize what they had talked about in the forms illustrated above. As you can see by the illustrations, this activity was very informal and done almost completely by the participants – yet the data retrieved from observing the group as well as the data produced by the charts was vital to this projects analysis.

Pie charts are visual methods used to demonstrate the distribution of various resources in relation to others. It can be a useful tool for evaluation and by using non-permeable materials it allows for flexibility, change and correction. By making use of a visual representation it includes participants who are not literate and gives them the opportunity to still be involved. It is even more useful when a language barrier exists between the researchers and participants as the data collected will be diagrammatically represented. In addition to allowing all participants to contribute to the process is it most valuable in obtaining social information.

For the study I am using as an example, the participants were asked to construct two pie charts. The first pie chart represented income, which included any sources from which the participants received their money, the second represented expenses or use of money. The translator (as these participants spoke isiZulu and I speak English) explained the process to the participants and before the exercise one of the researchers and a translator drew an example of a pie chart. As I was inside a hall instead of outside, we supplied the participants with string, prestik, masking tape and stones; however, this activity has been done before with merely sticks and sand.

The income and expenditure pie charts were used to immediately gain information about the use of money in the group. This activity would allow for further discussion based on the results as well as to inform the researchers of the variables of importance from the outset our study.

After explaining the process and leaving the materials with the group, I stepped back and allowed the participants to discuss the task (notice the concept of distanciation in action here). One participant (which we will refer to as Participant 1) took a leadership role and decided to generate a discussion among the group members. The translator and one researcher translated back to the other researchers while the participants were discussing the pie charts.

This exercise can also be used in conjunction with other activities, such as focus groups. This is what I did in my research; I asked the group to first discuss the issue, and then to visualize what they had talked about in the forms illustrated above. As you can see by the illustrations, this activity was very informal and done almost completely by the participants – yet the data retrieved from observing the group as well as the data produced by the charts was vital to this projects analysis.

Wednesday, 13 November 2013

Epistemology of participatory research

As mentioned in the last post, in this post, I will be discussing the epistemological principles of the participatory approach to conducting research. Epistemology refers to the nature of and scope of knowledge and the extent of what can be known. There are two epistemological positions: positivism vs. anti-positivism.

Positivism which arises from naturalism assumed the presence of an external reality with fixed properties independent of human beliefs and practices. According to this view, if contact with reality is distorted by subjective preference the resulting understanding is relegated to the status of mere belief or opinion, it is not science.

Knowledge Generated

As a result Positivism aimed to generate knowledge which sought to explain and predict what happens in the social world by searching for regularities, causal relationships between its constituent elements. It assumed an objective reality where its aim was to not understand the phenomena it studied but to provide reliable and valid conclusions about reality. Objectivism was thus the basic conviction that there is or must be some permanent, ahistorical matrix or framework to which we can ultimately appeal in determining the nature of rationality, knowledge, truth, reality, goodness, or rightness. It relied specifically on controlled experimentation in an attempt to secure its strictly objective, value free accounts of human phenomena. This was ensured by the adoption of methods that guaranteed that knowledge of reality was entirely objective, that is; uncontaminated by human wishes, fears, and evaluations became the goal.

Anti-positivism which is adopted by PR on the other hand offers an account of human agency which transcends positivist thinking to propose that knowledge is an interpretation which is continually situated within a living tradition. This means that the social world can only be understood from the point of view of the individuals who are directly involved in the activities which are to be studied. Additionally, it views individuals as continually situated within a specific ‘horizon’ of understanding grounded in cultural and personal presumptions. Therefore, PR rejects the notion of ‘observer’ characterizing positivist epistemology and suggests that any attempt at objectivity and value-free knowledge is misguided and unattainable. It proposes that one can only ‘understand’ by occupying the frame of reference of the participant in action. Additionally, one can only understand from the inside rather than the outside. Furthermore according to this view, despite best efforts at neutrality, cultural values and assumptions always permeate the field. Participatory research therefore provides a critique of existing theory, research and practice and recommends alternative models and methods positioned within a cultural and historical context.

According to PR knowledge is thus uncertain, evolving, contextual, and value laden. It values social theory that not only builds upon understandings but also extends this knowledge toward new insights that can form the basis for social action to improve practices. Additionally, it aims for scholarly publication where knowledge is presumed as being jointly owned with collaborators and hence shared with the community in ‘culturally appropriate modes’.

However, despite the well defined epistemological and ontological structure of participatory research, there are still challenges that the approach faces - these challenges will be discussed in the next post.

Positivism which arises from naturalism assumed the presence of an external reality with fixed properties independent of human beliefs and practices. According to this view, if contact with reality is distorted by subjective preference the resulting understanding is relegated to the status of mere belief or opinion, it is not science.

Knowledge Generated

As a result Positivism aimed to generate knowledge which sought to explain and predict what happens in the social world by searching for regularities, causal relationships between its constituent elements. It assumed an objective reality where its aim was to not understand the phenomena it studied but to provide reliable and valid conclusions about reality. Objectivism was thus the basic conviction that there is or must be some permanent, ahistorical matrix or framework to which we can ultimately appeal in determining the nature of rationality, knowledge, truth, reality, goodness, or rightness. It relied specifically on controlled experimentation in an attempt to secure its strictly objective, value free accounts of human phenomena. This was ensured by the adoption of methods that guaranteed that knowledge of reality was entirely objective, that is; uncontaminated by human wishes, fears, and evaluations became the goal.

Anti-positivism which is adopted by PR on the other hand offers an account of human agency which transcends positivist thinking to propose that knowledge is an interpretation which is continually situated within a living tradition. This means that the social world can only be understood from the point of view of the individuals who are directly involved in the activities which are to be studied. Additionally, it views individuals as continually situated within a specific ‘horizon’ of understanding grounded in cultural and personal presumptions. Therefore, PR rejects the notion of ‘observer’ characterizing positivist epistemology and suggests that any attempt at objectivity and value-free knowledge is misguided and unattainable. It proposes that one can only ‘understand’ by occupying the frame of reference of the participant in action. Additionally, one can only understand from the inside rather than the outside. Furthermore according to this view, despite best efforts at neutrality, cultural values and assumptions always permeate the field. Participatory research therefore provides a critique of existing theory, research and practice and recommends alternative models and methods positioned within a cultural and historical context.

According to PR knowledge is thus uncertain, evolving, contextual, and value laden. It values social theory that not only builds upon understandings but also extends this knowledge toward new insights that can form the basis for social action to improve practices. Additionally, it aims for scholarly publication where knowledge is presumed as being jointly owned with collaborators and hence shared with the community in ‘culturally appropriate modes’.

However, despite the well defined epistemological and ontological structure of participatory research, there are still challenges that the approach faces - these challenges will be discussed in the next post.

Monday, 11 November 2013

Concept of 'Local Knowledge' in participatory research

In the last post I discussed the concepts of conscientization and control and empowerment; all of these concepts are intricately interrelated, and thus they may seem similar or overlapping at certain points. In this post, I will be talking about the concept and use of local knowledge in participatory research. This is one of the core concepts of this approach, and thus careful consideration should be payed to it.

Local knowledge can be defined as a cumulative body of knowledge, know-how, practices, and presentations maintained and developed by peoples in a specific context”.

One of the central processes in the PR approach to conducting research interventions is accessing a community’s or an individual’s local knowledge, which the participators of the research possess; this knowledge is based on their daily practices and experiences in their own specific context and so knowledge which is essential to their survival in this context.

According to participatory researchers when researchers acknowledge and make use of local knowledge they fulfill two functions:

Firstly, concerning the participation of the research, (i.e. the community or individuals in a community), by using knowledge and resources that they already have and know about, they are less likely to be dependent on and controlled by external agencies, such as resources and knowledge; this also contributes to the success of the research, as well as the sustainability of the intervention. The significance of this point can be highlighted by looking again at the social orientated approach to viewing human action: this approach holds the view that human action can only be fully understood when the social, historical, and cultural context of the human who performs the action is also understood.

Secondly, by the researchers acknowledging this local knowledge, there is a possibility of shirting the balance of power away from the researcher. By using knowledge that the participants possess as opposed to knowledge possessed by the researchers, the researchers themselves are no longer in possession of the definitive perspective. This shift in the power dynamic has consequences for the outcome of the knowledge produced by the research; the participants are able to voice their own perspectives by proxy of the research publication, as well as influencing the possibility for changes in the future.

Tapping into the community’s local resources is essential if the research interventions aim to be thorough, well grounded, and within the grasp of the communities current abilities and potential abilities.

However, it must be mentioned that the communities which are the target of the research intervention are not the only entities which possess local knowledge. The researchers themselves also possess their own; a type of local knowledge that makes them competent in their own context. Practitioners of the PR approach are required to understand that their ways of doing and understand things are not more intrinsically correct that those belonging to the communities they are working with.

Local knowledge can be defined as a cumulative body of knowledge, know-how, practices, and presentations maintained and developed by peoples in a specific context”.

One of the central processes in the PR approach to conducting research interventions is accessing a community’s or an individual’s local knowledge, which the participators of the research possess; this knowledge is based on their daily practices and experiences in their own specific context and so knowledge which is essential to their survival in this context.

According to participatory researchers when researchers acknowledge and make use of local knowledge they fulfill two functions:

Firstly, concerning the participation of the research, (i.e. the community or individuals in a community), by using knowledge and resources that they already have and know about, they are less likely to be dependent on and controlled by external agencies, such as resources and knowledge; this also contributes to the success of the research, as well as the sustainability of the intervention. The significance of this point can be highlighted by looking again at the social orientated approach to viewing human action: this approach holds the view that human action can only be fully understood when the social, historical, and cultural context of the human who performs the action is also understood.

Secondly, by the researchers acknowledging this local knowledge, there is a possibility of shirting the balance of power away from the researcher. By using knowledge that the participants possess as opposed to knowledge possessed by the researchers, the researchers themselves are no longer in possession of the definitive perspective. This shift in the power dynamic has consequences for the outcome of the knowledge produced by the research; the participants are able to voice their own perspectives by proxy of the research publication, as well as influencing the possibility for changes in the future.

Tapping into the community’s local resources is essential if the research interventions aim to be thorough, well grounded, and within the grasp of the communities current abilities and potential abilities.

However, it must be mentioned that the communities which are the target of the research intervention are not the only entities which possess local knowledge. The researchers themselves also possess their own; a type of local knowledge that makes them competent in their own context. Practitioners of the PR approach are required to understand that their ways of doing and understand things are not more intrinsically correct that those belonging to the communities they are working with.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)