I've already mentioned doing interviews a couple times in the previous posts, but this entry will be dedicated to the topic itself. Semi-structured interviews are one of the main tools used in participatory research approaches, The reason why this method is called 'semi-structured' interviews, is because the questions determined a priori to the actual interview are merely used as a guide for the researcher, not a strict list that must be followed. Many of the questions are determined in the midst of the interview itself, determined by what the participant wants to talk about and what seems interesting to the researcher. Sometimes, the questions that are written before hand are deemed irrelevant in the particular interview, and can thus be skipped if the researcher thinks this is so.

There are two specific types of interviews that can be used effectively in participatory research; these are (a) individual semi-structured interviews and (b) key informant emi-structured interviews. I'll start off, as most people do, with (a).

Individual interviews are used to obtain representative information. As information that is obtained from individual interviews is more personal when compared to group interviews (for obvious reasons) it has a higher probability of revealing conflicts within the community as respondents may feel that can speak more freely without their neighbors present. One should attempt to interview as broadly representative a sample as possible; as participatory research places emphasis on those individuals who are at the very bottom of the society in which they are working, these individuals must be included in the interviews as well. One can also interview random people that happen to pass-by the researchers as these may reveal useful information and unexpected viewpoints.

The other type of interview that I will be talking about are interviews with individuals who are deemed 'key informants'. These types of semi-structured interviews are used to obtain special knowledge, as a key informant is anyone who has a special knowledge on a particular topic (such as a merchant on transportation and credit, midwife on birth control practices, or farmers on agricultural practices). Key informants are expected to be able to answer questions about the knowledge and behavior of others and specially about the operations of the broader systems in which the individual and their community is immersed. While it is possible that the information garnered by key informants may be misleading, they are still a may possible source of information for the participatory researcher. Valuable key informants are outsiders who live in the specific community, such as teachers or doctors, people from different communities, and individuals that have 'married in' to the community. They types of individuals usually have a more distanciated perspective on the practices within the community, and can thus offer more objective information on the community than the community members.

Thus concludes this post on semi-structured interviews and how they are essential to collecting data using the participatory research approach. This post was by no means a comprehensive account of interviews, as they are unexpectedly complex things to do correctly - however, it was just a basic idea of what they can provide a good researcher.

Thursday, 21 November 2013

Monday, 18 November 2013

Venn diagram exercise in participatory research

I haven't used this activity myself in research, but I can appreciate the value it may bring to the data collection process. As such, I will be merely explaining how one can go about using it instead of discussing it within an example itself.

To begin with, a Venn diagram (named after the man who came up with the concept) showed the key institutions and individuals in a community, as well as their relationships and importance for decision-making. It must be noted, however, that Venn diagrams may be a difficult concept to understand for those who have not been exposed to them before; be sure that everyone who is participating in the exercise fully understands the concept behind what they are doing.

There are multiple steps in the process of creating a Venn diagram, but the process of the participants constructing the diagram, as well as the end result of the diagram itself are both very rich sources of information. A basic structure of the steps to be taken when conducting a Venn diagram maximizing participation are as follows:

(1) Identify key institutions responsible for decisions in a community or organization;

(2) Identify the degree of contact and overlap between them in terms of decision-making. Overlap occurs if one institution asks or tells another to do something or if they have to cooperate in some way;

(3) Obtain information from secondary sources, group interviews, or from key informants;

(4) Cut out (or draw) circles to represent each institution or individual;

(5) Size of circles indicates importance or scope (separate circles = no contact; touching circles = information passes between institutions; small overlap = some cooperation in decision making; large overlap = considerable cooperation in decision making);

(6) Draw the Venn diagram first in pencil and adjust the size or arrangement of circles until the representation is accurate; when everyone is satisfied that it is accurate, go over it with a marker to make it more visible and easier to read;

(7) Encourage community members to draw their own Venn diagrams and compare them.

The image below is an example of a Venn diagram drawn by participants in a participatory research project on village water use and control in Sudan (not sure if it was in the north or south now though).

To begin with, a Venn diagram (named after the man who came up with the concept) showed the key institutions and individuals in a community, as well as their relationships and importance for decision-making. It must be noted, however, that Venn diagrams may be a difficult concept to understand for those who have not been exposed to them before; be sure that everyone who is participating in the exercise fully understands the concept behind what they are doing.

There are multiple steps in the process of creating a Venn diagram, but the process of the participants constructing the diagram, as well as the end result of the diagram itself are both very rich sources of information. A basic structure of the steps to be taken when conducting a Venn diagram maximizing participation are as follows:

(1) Identify key institutions responsible for decisions in a community or organization;

(2) Identify the degree of contact and overlap between them in terms of decision-making. Overlap occurs if one institution asks or tells another to do something or if they have to cooperate in some way;

(3) Obtain information from secondary sources, group interviews, or from key informants;

(4) Cut out (or draw) circles to represent each institution or individual;

(5) Size of circles indicates importance or scope (separate circles = no contact; touching circles = information passes between institutions; small overlap = some cooperation in decision making; large overlap = considerable cooperation in decision making);

(6) Draw the Venn diagram first in pencil and adjust the size or arrangement of circles until the representation is accurate; when everyone is satisfied that it is accurate, go over it with a marker to make it more visible and easier to read;

(7) Encourage community members to draw their own Venn diagrams and compare them.

The image below is an example of a Venn diagram drawn by participants in a participatory research project on village water use and control in Sudan (not sure if it was in the north or south now though).

Friday, 15 November 2013

Using a mapping exercise in participatory research

In this post, I will be talking about how one can use a mapping exercise in participatory research to gather data whilst maximizing participant participation in the research process. This exercise also makes full use of local perspectives and local knowledge, which is essential to the PR process, as I've already discussed in previous posts. I will, again, be using examples and images from some of my own research.

Mapping is a form of visual based data gathering usually through the use of pictures and symbolic indicators. This usually entails mapping out a community; this includes buildings, services, roads and communal areas. Participatory researchers have discussed the many ways in which maps can be used, such as to draw the spatial arrangement of houses. Mobility maps are used to identify the spatial mobility of communities or to access local knowledge on how people perceive their resources and places in their communities. Some see this commonly used method as a way in which participants construct and present their views. This tool also allows for participation of the entire group as it usually promotes discussion and the researchers can gain insight into the way participants generate ideas and then produce the information they want to include.

For the research I will be using as an example, the participants were asked to draw a map representing where all their money ‘went’, in other words where their money was spend or used and to represent it on a map, indicating how far or near they perceived these places to be. This technique was implemented in order to gain an overall perspective on where participants spend and use their money and also to generate discussion about how close or far these areas are considered to be.

During the process, the translator introduced the mapping exercise to the group of participants. Once again Participant 1 (as mentioned in the last post) took a leadership role and generated a discussion among the group in order to construct the map and answer the questions the researchers asked. At first the participants laughed as no one wanted the responsibility of drawing a map, after discussion Participant 1 and one other participant chose to use the paper and marker pens to create the map. The younger participant was recruited by the rest of the group to help as it seems she was able to write in English. The participants began by drawing roads and then buildings and houses, the younger participant then decided to label these areas after the researchers asked them to symbolically represent what they were drawing so to identify them. Although only two participants drew the map, Participant 1 consistently validated what was being drawn and referred back to the rest of the group.

As the above paragraphs imply, this research was heavily reliant on the participants knowledge and participation in the activity. Thus, the researcher's role was primarily one of observation and minimal facilitation. Again, this exercise enabled the researcher (me) to gain quite a lot of insight into the way the participants perceived their own monetary travelling. The original map was converted into a electronic version, which is a bit more clear - i've added this image below.

Mapping is a form of visual based data gathering usually through the use of pictures and symbolic indicators. This usually entails mapping out a community; this includes buildings, services, roads and communal areas. Participatory researchers have discussed the many ways in which maps can be used, such as to draw the spatial arrangement of houses. Mobility maps are used to identify the spatial mobility of communities or to access local knowledge on how people perceive their resources and places in their communities. Some see this commonly used method as a way in which participants construct and present their views. This tool also allows for participation of the entire group as it usually promotes discussion and the researchers can gain insight into the way participants generate ideas and then produce the information they want to include.

For the research I will be using as an example, the participants were asked to draw a map representing where all their money ‘went’, in other words where their money was spend or used and to represent it on a map, indicating how far or near they perceived these places to be. This technique was implemented in order to gain an overall perspective on where participants spend and use their money and also to generate discussion about how close or far these areas are considered to be.

During the process, the translator introduced the mapping exercise to the group of participants. Once again Participant 1 (as mentioned in the last post) took a leadership role and generated a discussion among the group in order to construct the map and answer the questions the researchers asked. At first the participants laughed as no one wanted the responsibility of drawing a map, after discussion Participant 1 and one other participant chose to use the paper and marker pens to create the map. The younger participant was recruited by the rest of the group to help as it seems she was able to write in English. The participants began by drawing roads and then buildings and houses, the younger participant then decided to label these areas after the researchers asked them to symbolically represent what they were drawing so to identify them. Although only two participants drew the map, Participant 1 consistently validated what was being drawn and referred back to the rest of the group.

As the above paragraphs imply, this research was heavily reliant on the participants knowledge and participation in the activity. Thus, the researcher's role was primarily one of observation and minimal facilitation. Again, this exercise enabled the researcher (me) to gain quite a lot of insight into the way the participants perceived their own monetary travelling. The original map was converted into a electronic version, which is a bit more clear - i've added this image below.

Thursday, 14 November 2013

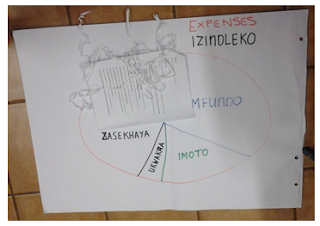

Using pie charts in participatory research

In this post I will be talking about the pie chart exercise as a method which one can gather data from when conducting participatory research. I will be using pictures and examples from some of my own research that I have conducted recently.

Pie charts are visual methods used to demonstrate the distribution of various resources in relation to others. It can be a useful tool for evaluation and by using non-permeable materials it allows for flexibility, change and correction. By making use of a visual representation it includes participants who are not literate and gives them the opportunity to still be involved. It is even more useful when a language barrier exists between the researchers and participants as the data collected will be diagrammatically represented. In addition to allowing all participants to contribute to the process is it most valuable in obtaining social information.

For the study I am using as an example, the participants were asked to construct two pie charts. The first pie chart represented income, which included any sources from which the participants received their money, the second represented expenses or use of money. The translator (as these participants spoke isiZulu and I speak English) explained the process to the participants and before the exercise one of the researchers and a translator drew an example of a pie chart. As I was inside a hall instead of outside, we supplied the participants with string, prestik, masking tape and stones; however, this activity has been done before with merely sticks and sand.

The income and expenditure pie charts were used to immediately gain information about the use of money in the group. This activity would allow for further discussion based on the results as well as to inform the researchers of the variables of importance from the outset our study.

After explaining the process and leaving the materials with the group, I stepped back and allowed the participants to discuss the task (notice the concept of distanciation in action here). One participant (which we will refer to as Participant 1) took a leadership role and decided to generate a discussion among the group members. The translator and one researcher translated back to the other researchers while the participants were discussing the pie charts.

This exercise can also be used in conjunction with other activities, such as focus groups. This is what I did in my research; I asked the group to first discuss the issue, and then to visualize what they had talked about in the forms illustrated above. As you can see by the illustrations, this activity was very informal and done almost completely by the participants – yet the data retrieved from observing the group as well as the data produced by the charts was vital to this projects analysis.

Pie charts are visual methods used to demonstrate the distribution of various resources in relation to others. It can be a useful tool for evaluation and by using non-permeable materials it allows for flexibility, change and correction. By making use of a visual representation it includes participants who are not literate and gives them the opportunity to still be involved. It is even more useful when a language barrier exists between the researchers and participants as the data collected will be diagrammatically represented. In addition to allowing all participants to contribute to the process is it most valuable in obtaining social information.

For the study I am using as an example, the participants were asked to construct two pie charts. The first pie chart represented income, which included any sources from which the participants received their money, the second represented expenses or use of money. The translator (as these participants spoke isiZulu and I speak English) explained the process to the participants and before the exercise one of the researchers and a translator drew an example of a pie chart. As I was inside a hall instead of outside, we supplied the participants with string, prestik, masking tape and stones; however, this activity has been done before with merely sticks and sand.

The income and expenditure pie charts were used to immediately gain information about the use of money in the group. This activity would allow for further discussion based on the results as well as to inform the researchers of the variables of importance from the outset our study.

After explaining the process and leaving the materials with the group, I stepped back and allowed the participants to discuss the task (notice the concept of distanciation in action here). One participant (which we will refer to as Participant 1) took a leadership role and decided to generate a discussion among the group members. The translator and one researcher translated back to the other researchers while the participants were discussing the pie charts.

This exercise can also be used in conjunction with other activities, such as focus groups. This is what I did in my research; I asked the group to first discuss the issue, and then to visualize what they had talked about in the forms illustrated above. As you can see by the illustrations, this activity was very informal and done almost completely by the participants – yet the data retrieved from observing the group as well as the data produced by the charts was vital to this projects analysis.

Ensuring rigor in participatory research

I know I said I will start discussing some techniques in the last post, but I forgot about the theory behind ensuring rigor in participatory research. Because scientific rigor is linked to the positivisitc approach, it is necessary to somewhat change the process of validity and reality when conducting participatory research. This is what will be discussed in the following post.

A challenge that arises in qualitative research is in assuring the quality and trustworthiness of research. A researcher may hope that the quality of research craftsmanship produces knowledge claims that are so powerful and convincing in their own right they carry the validation with them, like a strong piece of art. However, seldom does this actually occur. The value of qualitative research must be argued for and justified against established quantitative criteria. If lacking in this, qualitative researchers subject themselves to criticism from positivists who claim that qualitative research is merely a subjective assertion supported by unscientific method.

The concepts of reliability, validity and generalizability provide the fundamental framework for conducting and evaluating traditional quantitative research. Qualitative researchers however argue against these criteria, stating them as being reductionist and misinterpretative of the complex and diverse system of interrelationships. Consequently, they have instead replaced them with alternative criteria developed in response to their specific research ideals. This criteria includes ‘rigor’.

Rigor in qualitative research is often synonymous with the quantitative notion of validity. Validity is the degree to which research truly measures what it intends to measure. This criterion is based upon the supposition that the phenomena being measured possess ‘reality’ in an undisputed and objective sense. However, qualitative research argues that given the social world, it is inaccurate to assume the existence of one unequivocal reality to which all findings must respond. The question it raises instead is whose reality is the research addressing? .

By definition qualitative research is about ‘subjective interpretation’. PR enhances the validity of research through its participation of stakeholders. According to PR, since people are continually acting in the world in relation to others, human action is essentially social. Human action is viewed as a dialogical and dialectical process which seeks to access multiple voices and perspectives. Constructions of reality are viewed as being manifested through the reflective action of people and communities.

In PR subjects of the research are active participants throughout the research process. This procedure ensures validity by preventing the possibility of researchers to observe and interpret findings through the lens of their own interpretive frameworks. Hence, the theorizing of phenomena is not de-contextualized but rather fixed in individuals’ experiences and in their web of meanings. The integrity of the research process as well as the quality of the end product is based upon principles that allow a researcher to“acknowledge that trust and truth are fragile, while enabling them to engage with the messiness and complexity of data interpretation in ways that reflect the lives of participants. That is, valid research should take into account the sociality of human action and address the participative, relational and social aspects.

A much greater degree of validity is attained in PR when research participants are allowed to check the veracity of the material. This means that participants are provided feedback whereby they engage with the material and verify its accuracy. Through this verification process participants help formulate accounts that accurately represent their own experiences and perspectives. The validity of PR therefore exists within its joint and experiential nature, that is, valid research should be a reflection of an interpretation of human action.

Furthermore, PR is dependent on the level of practicality and the degree to which it engages within its socially valuable work. This is referred to as pragmatic validity, whereby in PR the practicality in the context of research is valued. The essential “truth” of the research pertains to the notion of research generating not only individualistic but institutional change. Thus, the concept of validity in PR has been broadened to accommodate a socially conscious and emancipatory discourse.

Another aim in PR is for it to demonstrate catalytic validity. Research that possesses catalytic validity is said to not only display the reality- altering impact of the inquiry process, it also directs this impact so that those under study will gain self- understanding and self- direction. In other words, PR should exhibit conscientization and display emancipatory intent. This means that the research should move those it studies in order understand the world and should be shaped in such a manner as to transform it.

A challenge that arises in qualitative research is in assuring the quality and trustworthiness of research. A researcher may hope that the quality of research craftsmanship produces knowledge claims that are so powerful and convincing in their own right they carry the validation with them, like a strong piece of art. However, seldom does this actually occur. The value of qualitative research must be argued for and justified against established quantitative criteria. If lacking in this, qualitative researchers subject themselves to criticism from positivists who claim that qualitative research is merely a subjective assertion supported by unscientific method.

The concepts of reliability, validity and generalizability provide the fundamental framework for conducting and evaluating traditional quantitative research. Qualitative researchers however argue against these criteria, stating them as being reductionist and misinterpretative of the complex and diverse system of interrelationships. Consequently, they have instead replaced them with alternative criteria developed in response to their specific research ideals. This criteria includes ‘rigor’.

Rigor in qualitative research is often synonymous with the quantitative notion of validity. Validity is the degree to which research truly measures what it intends to measure. This criterion is based upon the supposition that the phenomena being measured possess ‘reality’ in an undisputed and objective sense. However, qualitative research argues that given the social world, it is inaccurate to assume the existence of one unequivocal reality to which all findings must respond. The question it raises instead is whose reality is the research addressing? .

By definition qualitative research is about ‘subjective interpretation’. PR enhances the validity of research through its participation of stakeholders. According to PR, since people are continually acting in the world in relation to others, human action is essentially social. Human action is viewed as a dialogical and dialectical process which seeks to access multiple voices and perspectives. Constructions of reality are viewed as being manifested through the reflective action of people and communities.

In PR subjects of the research are active participants throughout the research process. This procedure ensures validity by preventing the possibility of researchers to observe and interpret findings through the lens of their own interpretive frameworks. Hence, the theorizing of phenomena is not de-contextualized but rather fixed in individuals’ experiences and in their web of meanings. The integrity of the research process as well as the quality of the end product is based upon principles that allow a researcher to“acknowledge that trust and truth are fragile, while enabling them to engage with the messiness and complexity of data interpretation in ways that reflect the lives of participants. That is, valid research should take into account the sociality of human action and address the participative, relational and social aspects.

A much greater degree of validity is attained in PR when research participants are allowed to check the veracity of the material. This means that participants are provided feedback whereby they engage with the material and verify its accuracy. Through this verification process participants help formulate accounts that accurately represent their own experiences and perspectives. The validity of PR therefore exists within its joint and experiential nature, that is, valid research should be a reflection of an interpretation of human action.

Furthermore, PR is dependent on the level of practicality and the degree to which it engages within its socially valuable work. This is referred to as pragmatic validity, whereby in PR the practicality in the context of research is valued. The essential “truth” of the research pertains to the notion of research generating not only individualistic but institutional change. Thus, the concept of validity in PR has been broadened to accommodate a socially conscious and emancipatory discourse.

Another aim in PR is for it to demonstrate catalytic validity. Research that possesses catalytic validity is said to not only display the reality- altering impact of the inquiry process, it also directs this impact so that those under study will gain self- understanding and self- direction. In other words, PR should exhibit conscientization and display emancipatory intent. This means that the research should move those it studies in order understand the world and should be shaped in such a manner as to transform it.

Wednesday, 13 November 2013

Challenges in participatory research

As hinted at in the last post, there are many challenges that participatory research and its practitioners must face. Mainly, these challenges have arisen because this research approach is relatively young and still needs to work out some 'kinks'. Some of these challenges will be discussed in the forthcoming post.

As some participatory researchers assert, it is common to hear of participatory researchers expressing frustration on the part of the community being apathetic towards the research process; thus, non-interest or apathy on behalf of the community is a challenge that PR practitioners must face. Participatory researchers also face a dilemma between building the capacity of the community as much as possible and report back to the research funders on the progress of the project; whilst educating funding agencies on the benefits of PR may make them more amiable to participatory research and true capacity building, this is currently a challenge PR faces.

Some of the core principles in PR, such as rapport building, often take a long time and thus can be constrained by lack of time and financial resources. Also concerning the financial resources of some PR phases, such as rapport building, are less likely to be supported by funders as they may not see it as an important part of the research process and thus it is up to the researchers to convince them of its importance. Although there is a focus on the ‘dispossessed’ (such as young children, the elderly, women) members of the community, many of the people do not end up being part of the research process and, subsequently, possibly vital sources of information are lost.

There may be participants who do not trust the researchers or feel that they have nothing to gain from participating in the activities and the overall research process often choose not to be involved in them at all, and, again, this is a loss of important information. Last in this itinerary of challenges, but not the least of them, is the issue of the lingering unbalanced power dynamics among the participants and the researchers, even if participation has been increased.

To conclude the posts i've written so far, it is evident from what was discussed that the participatory approach to conducting research is, at its core, fundamentally different from other research approaches, specifically that of positivism. For example, in contrast to the principles and concepts of conducting positivistic research, such as the researcher being a distant, disconnected, neutral entity who only looks at empirical sources of information and indirectly reinforces unequal power dynamics in research, the participatory researcher believes in the principles of verstehen and distanciation, maximizing the role of the participants in the research in order to make use of their own local knowledge so as to decrease the power dynamics between researchers and participants and to maximize the chance of sustainable empowerment in the community they are working with.

The participatory approach also adopts some principles from the social approach to understand human action, such as the fact that individuals are not always aware of the meaning and reason behind their own actions and that in order to understand an action; one must understand the cultural and social conventions and institutions that indirectly determine the intent of the action. The ontological (nature of reality) and epistemological (nature of knowledge) structure of the participatory approach and subsequently how knowledge, using the participatory approach, is generated. Lastly, in this post, some of the challenges of the PR approach – which appeared to be primarily practical issues – were discussed. In the subsequent posts, I will be discussing certain participatory research techniques that can be used which maximize participant participation.

As some participatory researchers assert, it is common to hear of participatory researchers expressing frustration on the part of the community being apathetic towards the research process; thus, non-interest or apathy on behalf of the community is a challenge that PR practitioners must face. Participatory researchers also face a dilemma between building the capacity of the community as much as possible and report back to the research funders on the progress of the project; whilst educating funding agencies on the benefits of PR may make them more amiable to participatory research and true capacity building, this is currently a challenge PR faces.

Some of the core principles in PR, such as rapport building, often take a long time and thus can be constrained by lack of time and financial resources. Also concerning the financial resources of some PR phases, such as rapport building, are less likely to be supported by funders as they may not see it as an important part of the research process and thus it is up to the researchers to convince them of its importance. Although there is a focus on the ‘dispossessed’ (such as young children, the elderly, women) members of the community, many of the people do not end up being part of the research process and, subsequently, possibly vital sources of information are lost.

There may be participants who do not trust the researchers or feel that they have nothing to gain from participating in the activities and the overall research process often choose not to be involved in them at all, and, again, this is a loss of important information. Last in this itinerary of challenges, but not the least of them, is the issue of the lingering unbalanced power dynamics among the participants and the researchers, even if participation has been increased.

To conclude the posts i've written so far, it is evident from what was discussed that the participatory approach to conducting research is, at its core, fundamentally different from other research approaches, specifically that of positivism. For example, in contrast to the principles and concepts of conducting positivistic research, such as the researcher being a distant, disconnected, neutral entity who only looks at empirical sources of information and indirectly reinforces unequal power dynamics in research, the participatory researcher believes in the principles of verstehen and distanciation, maximizing the role of the participants in the research in order to make use of their own local knowledge so as to decrease the power dynamics between researchers and participants and to maximize the chance of sustainable empowerment in the community they are working with.

The participatory approach also adopts some principles from the social approach to understand human action, such as the fact that individuals are not always aware of the meaning and reason behind their own actions and that in order to understand an action; one must understand the cultural and social conventions and institutions that indirectly determine the intent of the action. The ontological (nature of reality) and epistemological (nature of knowledge) structure of the participatory approach and subsequently how knowledge, using the participatory approach, is generated. Lastly, in this post, some of the challenges of the PR approach – which appeared to be primarily practical issues – were discussed. In the subsequent posts, I will be discussing certain participatory research techniques that can be used which maximize participant participation.

Labels:

Action,

Background,

Challenges in PR,

Commonsense psychology,

Conclusion,

Empistemology,

Empowerment,

Folk Psychology,

Human Action,

Humanism,

Introduction,

Knowledge,

Ontology,

Participatory Research,

Social

Epistemology of participatory research

As mentioned in the last post, in this post, I will be discussing the epistemological principles of the participatory approach to conducting research. Epistemology refers to the nature of and scope of knowledge and the extent of what can be known. There are two epistemological positions: positivism vs. anti-positivism.

Positivism which arises from naturalism assumed the presence of an external reality with fixed properties independent of human beliefs and practices. According to this view, if contact with reality is distorted by subjective preference the resulting understanding is relegated to the status of mere belief or opinion, it is not science.

Knowledge Generated

As a result Positivism aimed to generate knowledge which sought to explain and predict what happens in the social world by searching for regularities, causal relationships between its constituent elements. It assumed an objective reality where its aim was to not understand the phenomena it studied but to provide reliable and valid conclusions about reality. Objectivism was thus the basic conviction that there is or must be some permanent, ahistorical matrix or framework to which we can ultimately appeal in determining the nature of rationality, knowledge, truth, reality, goodness, or rightness. It relied specifically on controlled experimentation in an attempt to secure its strictly objective, value free accounts of human phenomena. This was ensured by the adoption of methods that guaranteed that knowledge of reality was entirely objective, that is; uncontaminated by human wishes, fears, and evaluations became the goal.

Anti-positivism which is adopted by PR on the other hand offers an account of human agency which transcends positivist thinking to propose that knowledge is an interpretation which is continually situated within a living tradition. This means that the social world can only be understood from the point of view of the individuals who are directly involved in the activities which are to be studied. Additionally, it views individuals as continually situated within a specific ‘horizon’ of understanding grounded in cultural and personal presumptions. Therefore, PR rejects the notion of ‘observer’ characterizing positivist epistemology and suggests that any attempt at objectivity and value-free knowledge is misguided and unattainable. It proposes that one can only ‘understand’ by occupying the frame of reference of the participant in action. Additionally, one can only understand from the inside rather than the outside. Furthermore according to this view, despite best efforts at neutrality, cultural values and assumptions always permeate the field. Participatory research therefore provides a critique of existing theory, research and practice and recommends alternative models and methods positioned within a cultural and historical context.

According to PR knowledge is thus uncertain, evolving, contextual, and value laden. It values social theory that not only builds upon understandings but also extends this knowledge toward new insights that can form the basis for social action to improve practices. Additionally, it aims for scholarly publication where knowledge is presumed as being jointly owned with collaborators and hence shared with the community in ‘culturally appropriate modes’.

However, despite the well defined epistemological and ontological structure of participatory research, there are still challenges that the approach faces - these challenges will be discussed in the next post.

Positivism which arises from naturalism assumed the presence of an external reality with fixed properties independent of human beliefs and practices. According to this view, if contact with reality is distorted by subjective preference the resulting understanding is relegated to the status of mere belief or opinion, it is not science.

Knowledge Generated

As a result Positivism aimed to generate knowledge which sought to explain and predict what happens in the social world by searching for regularities, causal relationships between its constituent elements. It assumed an objective reality where its aim was to not understand the phenomena it studied but to provide reliable and valid conclusions about reality. Objectivism was thus the basic conviction that there is or must be some permanent, ahistorical matrix or framework to which we can ultimately appeal in determining the nature of rationality, knowledge, truth, reality, goodness, or rightness. It relied specifically on controlled experimentation in an attempt to secure its strictly objective, value free accounts of human phenomena. This was ensured by the adoption of methods that guaranteed that knowledge of reality was entirely objective, that is; uncontaminated by human wishes, fears, and evaluations became the goal.

Anti-positivism which is adopted by PR on the other hand offers an account of human agency which transcends positivist thinking to propose that knowledge is an interpretation which is continually situated within a living tradition. This means that the social world can only be understood from the point of view of the individuals who are directly involved in the activities which are to be studied. Additionally, it views individuals as continually situated within a specific ‘horizon’ of understanding grounded in cultural and personal presumptions. Therefore, PR rejects the notion of ‘observer’ characterizing positivist epistemology and suggests that any attempt at objectivity and value-free knowledge is misguided and unattainable. It proposes that one can only ‘understand’ by occupying the frame of reference of the participant in action. Additionally, one can only understand from the inside rather than the outside. Furthermore according to this view, despite best efforts at neutrality, cultural values and assumptions always permeate the field. Participatory research therefore provides a critique of existing theory, research and practice and recommends alternative models and methods positioned within a cultural and historical context.

According to PR knowledge is thus uncertain, evolving, contextual, and value laden. It values social theory that not only builds upon understandings but also extends this knowledge toward new insights that can form the basis for social action to improve practices. Additionally, it aims for scholarly publication where knowledge is presumed as being jointly owned with collaborators and hence shared with the community in ‘culturally appropriate modes’.

However, despite the well defined epistemological and ontological structure of participatory research, there are still challenges that the approach faces - these challenges will be discussed in the next post.

Ontology of participatory research

In this post I will be discussing some of the ontological aspects of the participatory research approach. Ontology refers to the nature of reality or existence and what can be known about it . One can distinguish between two approaches to ontology: realism versus non-realism

Nature of Reality

Realism, which arises from naturalism, has dominated much of scientific research. It proposes that the social world external to individual cognition is a real world made up of hard, tangible and relatively immutable structures. This was a key aspect of a naturalism which involved the 'disenchantment of the world', a process which moved away from the rich appearance of phenomena to regard the world objectively as consisting of inherently meaningless objects which are in causal interaction with one another.

The social world thus for the realist exists independently of an individual’s appreciation of it and the social world has an existence which is as hard and concrete as the natural world. Contrarily, nominalism assumes that the social world external to individual cognition is made of nothing more than names, concepts and labels which are used to structure reality.

Participatory research adopts the nominalist approach and further goes on to suggest that the social world inhabited by people is rather context bound, relational and situated. Participatory research argues that social reality is historically constructed, recognizing that specific interests drive current social practices. Thus social reality is viewed as being constructed through social perceptions making it subjective.

Subsequently, historical and reflective methods are preferred in participatory research as they uncover that social practices are neither natural nor inevitable, that is; society is a human construction to be critiqued and changed on the basis of more-inclusive interests.

While this post is by no means a complete summary of the ontology of participatory research, it is a starting point for those who wish to learn the basics. In the next post, I will be discussing the epistemology of the participatory research approach.

Nature of Reality

Realism, which arises from naturalism, has dominated much of scientific research. It proposes that the social world external to individual cognition is a real world made up of hard, tangible and relatively immutable structures. This was a key aspect of a naturalism which involved the 'disenchantment of the world', a process which moved away from the rich appearance of phenomena to regard the world objectively as consisting of inherently meaningless objects which are in causal interaction with one another.

The social world thus for the realist exists independently of an individual’s appreciation of it and the social world has an existence which is as hard and concrete as the natural world. Contrarily, nominalism assumes that the social world external to individual cognition is made of nothing more than names, concepts and labels which are used to structure reality.

Participatory research adopts the nominalist approach and further goes on to suggest that the social world inhabited by people is rather context bound, relational and situated. Participatory research argues that social reality is historically constructed, recognizing that specific interests drive current social practices. Thus social reality is viewed as being constructed through social perceptions making it subjective.

Subsequently, historical and reflective methods are preferred in participatory research as they uncover that social practices are neither natural nor inevitable, that is; society is a human construction to be critiqued and changed on the basis of more-inclusive interests.

While this post is by no means a complete summary of the ontology of participatory research, it is a starting point for those who wish to learn the basics. In the next post, I will be discussing the epistemology of the participatory research approach.

Tuesday, 12 November 2013

Distanciation in participatory research

In this post I shall be discussing the rather positivist concept of distanciation. While I did argue that positivist research is outdated and inadequate for the purposes of studying human action, there are some aspects, when used in conjunction with more essentially social concepts, that are helpful.

It has been theorized by multiple authors that interpretation of a certain context surpasses the limitations imposed by simply understanding a context. This type of interpretation has been termed the ‘hermeneutical function of distanciation’. The concept of distanciation is important to participatory research as it allows the researcher to find things, such as patterns of behaviour, they could not in a state of subjective empathy.

By adopting the concept of distanciation in their research, the PR practitioner may be able to discover patterns that occur across different contexts that they would not be able to find if they were situated within on particular context; in other words, when the research is subjective and empathizes with one certain community – this is also known as Verstehen. Distanciation also allows the researcher to ask questions and develop perspectives of the ‘bigger picture’ and to gain an understanding as to why intentional actions are performed in the context they are conducting their research in.

Distanciation does not only mean that the researcher places themselves outside of the present context; participatory researchers also make use of temporal-distanciation, which gives us, as it has been stated, “the benefit of hindsight”. This temporal-distanciation allows the PR researcher to view the current context in relation to the historical context of the community. It also allows the researcher to have a better understanding of the causal influences of events and patterns (that these events comprise) and how these patterns could be linked across time.

By distancing themselves from the participants and the context of the research, the participatory researcher has a greater possibility of understanding why participants perform certain actions, such as rituals, ceremonies, and superstitions. As the actor often doesn't know why (as in they do not know the reason for their action) they do the action, as they are merely conforming to conventional practices within their community, asking them directly why they do something is not the surest method of the researcher gaining a true understanding of the participant’s reasoning. Thus, as it has been suggested, distanciation has the ability to reveal the role of convention and tradition in the crafting of action.

Now that a basic theoretical overview on the participatory research approach has been in the last ten or so posts, I shall soon be moving onto a discussion concerning the ontological and epistemological views that are held within the PR approach. Stay tuned for more : }

It has been theorized by multiple authors that interpretation of a certain context surpasses the limitations imposed by simply understanding a context. This type of interpretation has been termed the ‘hermeneutical function of distanciation’. The concept of distanciation is important to participatory research as it allows the researcher to find things, such as patterns of behaviour, they could not in a state of subjective empathy.

By adopting the concept of distanciation in their research, the PR practitioner may be able to discover patterns that occur across different contexts that they would not be able to find if they were situated within on particular context; in other words, when the research is subjective and empathizes with one certain community – this is also known as Verstehen. Distanciation also allows the researcher to ask questions and develop perspectives of the ‘bigger picture’ and to gain an understanding as to why intentional actions are performed in the context they are conducting their research in.

Distanciation does not only mean that the researcher places themselves outside of the present context; participatory researchers also make use of temporal-distanciation, which gives us, as it has been stated, “the benefit of hindsight”. This temporal-distanciation allows the PR researcher to view the current context in relation to the historical context of the community. It also allows the researcher to have a better understanding of the causal influences of events and patterns (that these events comprise) and how these patterns could be linked across time.

By distancing themselves from the participants and the context of the research, the participatory researcher has a greater possibility of understanding why participants perform certain actions, such as rituals, ceremonies, and superstitions. As the actor often doesn't know why (as in they do not know the reason for their action) they do the action, as they are merely conforming to conventional practices within their community, asking them directly why they do something is not the surest method of the researcher gaining a true understanding of the participant’s reasoning. Thus, as it has been suggested, distanciation has the ability to reveal the role of convention and tradition in the crafting of action.

Now that a basic theoretical overview on the participatory research approach has been in the last ten or so posts, I shall soon be moving onto a discussion concerning the ontological and epistemological views that are held within the PR approach. Stay tuned for more : }

Praxis: action <-> research

In this post I will be talking about the concept of praxis. In short, praxis means action through research, and research through action (thus, the funny little <-> arrows in the title). This is one of the main ideals of participatory research, and is also underlying to participatory action research - which is PR but with a focus on action. However, that's a somewhat different approach - but the concept is still applicable here. Praxis, as we will see, is closely linked to the concept of conscientization which was discussed previously.

In contrast to mainstream scientific method, which attempts to control the effects of the researcher’s presence (as much as possible to the extent that the research is not there at all), the PR approach views the effects that a researcher has on the research intervention as something that is impossible to deny or overcome, and thus researcher’s effect on the intervention should be taken into account.

Practitioners of the PR approach suggest that just be asking a person questions, there is a possibility to invoke within them different ways to view a specific situation. This type of thinking may have a ‘reflexive effect’ on the research participators; the term reflexive here is closely linked to the concept of conscientization, in that it refers to the way in which the research process is conducted can have an influence upon the context of the research.

Followers of the participatory research approach also believe that the entire research process is reflexive in that the theories developed and the outcomes of research projects influence our perception of what possible actions are available to take. Similarly, they believe that when participants (either an individual or members of a community) are involved in a research process they develop a self-understanding which has a possibility to affect the actions they may take.

The process involved in an individual or a community attempting to analyze their own problems is seen by practitioners of the PR approach as the beginning of a possible path to action.

Participatory researchers attempt to harness this reflexivity and use it as a vehicle of change. The interactive relationship that exists between research and action is called ‘praxis’. Thus, praxis can be defined as a form of social intervention that is at one and the same time an idea and an action.

It has been suggested that for praxis to be possible, not only must theory illuminate the lived experience of progressive social groups, it must also be illuminated by their struggles. This can be extended to suggest that PR researchers using the concept of praxis should be open-ended, non-dogmatic, informing, grounded in everyday life events, and have a desire to better those some researchers term the ‘dispossessed’.

In contrast to mainstream scientific method, which attempts to control the effects of the researcher’s presence (as much as possible to the extent that the research is not there at all), the PR approach views the effects that a researcher has on the research intervention as something that is impossible to deny or overcome, and thus researcher’s effect on the intervention should be taken into account.

Practitioners of the PR approach suggest that just be asking a person questions, there is a possibility to invoke within them different ways to view a specific situation. This type of thinking may have a ‘reflexive effect’ on the research participators; the term reflexive here is closely linked to the concept of conscientization, in that it refers to the way in which the research process is conducted can have an influence upon the context of the research.

Followers of the participatory research approach also believe that the entire research process is reflexive in that the theories developed and the outcomes of research projects influence our perception of what possible actions are available to take. Similarly, they believe that when participants (either an individual or members of a community) are involved in a research process they develop a self-understanding which has a possibility to affect the actions they may take.

The process involved in an individual or a community attempting to analyze their own problems is seen by practitioners of the PR approach as the beginning of a possible path to action.

Participatory researchers attempt to harness this reflexivity and use it as a vehicle of change. The interactive relationship that exists between research and action is called ‘praxis’. Thus, praxis can be defined as a form of social intervention that is at one and the same time an idea and an action.

It has been suggested that for praxis to be possible, not only must theory illuminate the lived experience of progressive social groups, it must also be illuminated by their struggles. This can be extended to suggest that PR researchers using the concept of praxis should be open-ended, non-dogmatic, informing, grounded in everyday life events, and have a desire to better those some researchers term the ‘dispossessed’.

For persons, as autonomous beings, have a moral right to participate in decisions that claim to generate knowledge about them… such a right protects them… from being managed and manipulated… the moral principle of respect for persons is most fully honoured when power is shared not only in the application… but also in the generation of knowledge.

In the next post, I will be discussing the concepts of distaciation and empathetic understanding (also known as Verstehen).

Monday, 11 November 2013

Concept of 'Local Knowledge' in participatory research

In the last post I discussed the concepts of conscientization and control and empowerment; all of these concepts are intricately interrelated, and thus they may seem similar or overlapping at certain points. In this post, I will be talking about the concept and use of local knowledge in participatory research. This is one of the core concepts of this approach, and thus careful consideration should be payed to it.

Local knowledge can be defined as a cumulative body of knowledge, know-how, practices, and presentations maintained and developed by peoples in a specific context”.

One of the central processes in the PR approach to conducting research interventions is accessing a community’s or an individual’s local knowledge, which the participators of the research possess; this knowledge is based on their daily practices and experiences in their own specific context and so knowledge which is essential to their survival in this context.

According to participatory researchers when researchers acknowledge and make use of local knowledge they fulfill two functions:

Firstly, concerning the participation of the research, (i.e. the community or individuals in a community), by using knowledge and resources that they already have and know about, they are less likely to be dependent on and controlled by external agencies, such as resources and knowledge; this also contributes to the success of the research, as well as the sustainability of the intervention. The significance of this point can be highlighted by looking again at the social orientated approach to viewing human action: this approach holds the view that human action can only be fully understood when the social, historical, and cultural context of the human who performs the action is also understood.

Secondly, by the researchers acknowledging this local knowledge, there is a possibility of shirting the balance of power away from the researcher. By using knowledge that the participants possess as opposed to knowledge possessed by the researchers, the researchers themselves are no longer in possession of the definitive perspective. This shift in the power dynamic has consequences for the outcome of the knowledge produced by the research; the participants are able to voice their own perspectives by proxy of the research publication, as well as influencing the possibility for changes in the future.

Tapping into the community’s local resources is essential if the research interventions aim to be thorough, well grounded, and within the grasp of the communities current abilities and potential abilities.

However, it must be mentioned that the communities which are the target of the research intervention are not the only entities which possess local knowledge. The researchers themselves also possess their own; a type of local knowledge that makes them competent in their own context. Practitioners of the PR approach are required to understand that their ways of doing and understand things are not more intrinsically correct that those belonging to the communities they are working with.

Local knowledge can be defined as a cumulative body of knowledge, know-how, practices, and presentations maintained and developed by peoples in a specific context”.

One of the central processes in the PR approach to conducting research interventions is accessing a community’s or an individual’s local knowledge, which the participators of the research possess; this knowledge is based on their daily practices and experiences in their own specific context and so knowledge which is essential to their survival in this context.

According to participatory researchers when researchers acknowledge and make use of local knowledge they fulfill two functions:

Firstly, concerning the participation of the research, (i.e. the community or individuals in a community), by using knowledge and resources that they already have and know about, they are less likely to be dependent on and controlled by external agencies, such as resources and knowledge; this also contributes to the success of the research, as well as the sustainability of the intervention. The significance of this point can be highlighted by looking again at the social orientated approach to viewing human action: this approach holds the view that human action can only be fully understood when the social, historical, and cultural context of the human who performs the action is also understood.

Secondly, by the researchers acknowledging this local knowledge, there is a possibility of shirting the balance of power away from the researcher. By using knowledge that the participants possess as opposed to knowledge possessed by the researchers, the researchers themselves are no longer in possession of the definitive perspective. This shift in the power dynamic has consequences for the outcome of the knowledge produced by the research; the participants are able to voice their own perspectives by proxy of the research publication, as well as influencing the possibility for changes in the future.

Tapping into the community’s local resources is essential if the research interventions aim to be thorough, well grounded, and within the grasp of the communities current abilities and potential abilities.

However, it must be mentioned that the communities which are the target of the research intervention are not the only entities which possess local knowledge. The researchers themselves also possess their own; a type of local knowledge that makes them competent in their own context. Practitioners of the PR approach are required to understand that their ways of doing and understand things are not more intrinsically correct that those belonging to the communities they are working with.

Sunday, 10 November 2013

Concepts of conscientization and control and empowerment

In this post I will be discussing the concepts of (a) conscientization and (b) control and empowerment and how they are used within the participatory research process.

Conscientization

Conscientization, or critical consciousness, is a concept developed by Paulo Freire and is grounded in Marxist critical theory. Freire wrote about various ways in which people respond to cultural deprivation and oppression. To Freire, conscientization is the antithesis to oppression. The concept of conscientization within the community context focuses on the community members achieving an in-depth understanding of the world, which would allow them a greater awareness of their sociocultural realities and are able to critically engage in socio-cultural analysis, and cultural re-development and transformation.

Thus, in the opinion of the practitioners of the participatory research approach, conscientization, or the raising or critical awareness, or self reflexivity, is an essential component in any research project or intervention that has the aim of being sustainable and effective in being an agent of liberation. Furthermore, placing focus on the concept of conscientization means adopting the view and stance that people are active agents in the research process. The desired practical outcome of the concept within the PR approach is that if people are involved in an analysis of their own realities, they have a chance to develop their understanding and a capacity to act to improve that reality.

Control and Empowerment

The term empowerment is often misunderstood by those who see it, if they ever do: a literature review conducted on articles which focus on empowerment resulted in no clear definition of the concept, and the definitions found were often narrow and limited to one field. Participatory researchers assert that empowerment is a complex and multifaceted concept and that it is a process that challenged our assumptions about the way things are can be, it challenges our basic assumptions about power, helping, and achieving.

Generally, participatory research is used when there is a motivation or need to bring about some form of cooperative action, usually between a certain community and an external (as in outside of that community) agent, which could be a service or resources, with the primary intention of improving the conditions in the community. It is not surprise then that empowerment is intricately linked with participation, just as participation is closely connected to the concept of conscientization and reflexivity.

The PR research stands between external agents, such as the governments and NGO’s, on the one side, and the community they are working with on the other side. Through the participatory research process, communities are able to move themselves from a position of marginalization to a position of greater power.

Practitioners of the PR approach believe one of their main tasks is to discover what skills and resources the community possess; in other words, the capacity of the community. They also believe that is it their responsibility in working with the community to enhance these skills and resources to benefit the community. Combined, this process is called capacity-building, and it can take many forms; however, simply put, capacity building can be defined as a process that ‘enables’ people to participate actively in development processes and usually entails some form of skills enhancement.

Thus, having knowledge about an existing, possibly oppressive, reality and being part of the process of knowledge production can, according to the PR approach, result in empowerment; when people participate in determining their own future, they are empowered – at least to some extent.

In the next post I will be discussing the concept of local knowledge. This concept gets a post of its own because it is vital to participatory research.

Conscientization

Conscientization, or critical consciousness, is a concept developed by Paulo Freire and is grounded in Marxist critical theory. Freire wrote about various ways in which people respond to cultural deprivation and oppression. To Freire, conscientization is the antithesis to oppression. The concept of conscientization within the community context focuses on the community members achieving an in-depth understanding of the world, which would allow them a greater awareness of their sociocultural realities and are able to critically engage in socio-cultural analysis, and cultural re-development and transformation.

Thus, in the opinion of the practitioners of the participatory research approach, conscientization, or the raising or critical awareness, or self reflexivity, is an essential component in any research project or intervention that has the aim of being sustainable and effective in being an agent of liberation. Furthermore, placing focus on the concept of conscientization means adopting the view and stance that people are active agents in the research process. The desired practical outcome of the concept within the PR approach is that if people are involved in an analysis of their own realities, they have a chance to develop their understanding and a capacity to act to improve that reality.

Control and Empowerment

The term empowerment is often misunderstood by those who see it, if they ever do: a literature review conducted on articles which focus on empowerment resulted in no clear definition of the concept, and the definitions found were often narrow and limited to one field. Participatory researchers assert that empowerment is a complex and multifaceted concept and that it is a process that challenged our assumptions about the way things are can be, it challenges our basic assumptions about power, helping, and achieving.

Generally, participatory research is used when there is a motivation or need to bring about some form of cooperative action, usually between a certain community and an external (as in outside of that community) agent, which could be a service or resources, with the primary intention of improving the conditions in the community. It is not surprise then that empowerment is intricately linked with participation, just as participation is closely connected to the concept of conscientization and reflexivity.

The PR research stands between external agents, such as the governments and NGO’s, on the one side, and the community they are working with on the other side. Through the participatory research process, communities are able to move themselves from a position of marginalization to a position of greater power.

Practitioners of the PR approach believe one of their main tasks is to discover what skills and resources the community possess; in other words, the capacity of the community. They also believe that is it their responsibility in working with the community to enhance these skills and resources to benefit the community. Combined, this process is called capacity-building, and it can take many forms; however, simply put, capacity building can be defined as a process that ‘enables’ people to participate actively in development processes and usually entails some form of skills enhancement.

Thus, having knowledge about an existing, possibly oppressive, reality and being part of the process of knowledge production can, according to the PR approach, result in empowerment; when people participate in determining their own future, they are empowered – at least to some extent.

In the next post I will be discussing the concept of local knowledge. This concept gets a post of its own because it is vital to participatory research.

Participatory Research

Finally, we are able to discuss the actual topic of this blog – the participatory research approach. In the previous posts, I have discussed the theory that has led up to this point; the inadequacy of the positivistic approach, and the essentially social nature of human activity. However, before a discussion on what participatory research is, a definition of what participation is must be established.

There are many definitions of ‘participation’ to be found, but for the purpose of this report, participation shall be defined as “people’s involvement in decision making about what should be done and how, in implementation of the project, in sharing in the benefits of a project, and in evaluation of the project”.

Participatory research has emerged as an alternative to positivistic systems of knowledge production by challenging some of the core values of the traditional, mainstream, social science research methodology. The core values that participatory challenges are the belief in researchers must be neutral, objective, and value-free. Rather, the practitioners of the participatory research approach recognise average people as researchers themselves; researchers in pursuit of answers to the questions of their daily lives, and their own problems. In addition, research projects and strategies which place emphasis on participation are gaining increasing respect and attention, primarily in health research, in both developed and developing nations. In traditional research, such as that conducted within the positivistic domain, it is too often the case that the conclusions and recommendations made have been inappropriate to the context; the main cause of this is the failure to take into account the local priorities, processes and perspectives. In stark contrast, the participatory approach places emphasis on a ‘bottom-up’ approach where there is a focus on locally defined priorities and local perspectives. This involvement of local people as participants in the research process has been shown to enhance the effectiveness of the research as well as to save money and time in the long term.

As participatory research places such an emphasis on the ‘local’, it is no surprise that the methods used in participatory research are designed to bring the researcher to understand the specific qualities of a given context or person and the experiences, issues, and problems that are unique to that context or person. What is meant by the term ‘understand’ in the previous statement is that the researcher gains knowledge of an individual’s life, or even a situation in specific community, so that the researcher’s perspectives, in a sense, becomes that of the research participants. In other words, the methods designed for, and used in, participatory research attempt to maximise the empathy of the researcher.

Practitioners of the participatory research approach make use of some core concepts, such as, but not limited to: conscientization, control and empowerment, local knowledge, praxis (research as action) and context. The next posts will encompass some of these core concepts and will discuss how they are useful and essential to participatory research.

There are many definitions of ‘participation’ to be found, but for the purpose of this report, participation shall be defined as “people’s involvement in decision making about what should be done and how, in implementation of the project, in sharing in the benefits of a project, and in evaluation of the project”.

Participatory research has emerged as an alternative to positivistic systems of knowledge production by challenging some of the core values of the traditional, mainstream, social science research methodology. The core values that participatory challenges are the belief in researchers must be neutral, objective, and value-free. Rather, the practitioners of the participatory research approach recognise average people as researchers themselves; researchers in pursuit of answers to the questions of their daily lives, and their own problems. In addition, research projects and strategies which place emphasis on participation are gaining increasing respect and attention, primarily in health research, in both developed and developing nations. In traditional research, such as that conducted within the positivistic domain, it is too often the case that the conclusions and recommendations made have been inappropriate to the context; the main cause of this is the failure to take into account the local priorities, processes and perspectives. In stark contrast, the participatory approach places emphasis on a ‘bottom-up’ approach where there is a focus on locally defined priorities and local perspectives. This involvement of local people as participants in the research process has been shown to enhance the effectiveness of the research as well as to save money and time in the long term.

As participatory research places such an emphasis on the ‘local’, it is no surprise that the methods used in participatory research are designed to bring the researcher to understand the specific qualities of a given context or person and the experiences, issues, and problems that are unique to that context or person. What is meant by the term ‘understand’ in the previous statement is that the researcher gains knowledge of an individual’s life, or even a situation in specific community, so that the researcher’s perspectives, in a sense, becomes that of the research participants. In other words, the methods designed for, and used in, participatory research attempt to maximise the empathy of the researcher.

Practitioners of the participatory research approach make use of some core concepts, such as, but not limited to: conscientization, control and empowerment, local knowledge, praxis (research as action) and context. The next posts will encompass some of these core concepts and will discuss how they are useful and essential to participatory research.

Saturday, 9 November 2013

The social approach to understanding human action: part two

The previous post on the social approach to understanding human action introduced us to the topic, but ended off with a comment on intelligibility being necessary for understanding human action. This post will elucidate this comment and discuss it further.